B-Cubed software development guide

This guide specifies high-level requirements for software, computational tools and resources developed for B-Cubed (referred to in the sections as “software”) to ensure that the produced software meets the intended quality, openness, portability and reusability.

Suggestion citation:

Huybrechts P, Trekels M, Abraham L, Desmet P (2024). B-Cubed software development guide. https://docs.b-cubed.eu/guides/software-development/

Introduction

These requirements were carefully selected from numerous existing best practices and guidelines, and aim to promote a consistent open source development cycle that allows collaboration and reuse within and outside of the consortium. Emphasis is placed on standardized metadata (files) that make it easier for both humans and search engines to find the software, and thus to increase its discoverability and reuse. In this same vein, emphasis is placed on the portability of the produced software to make sure it is functional on different platforms now and in the future with minimal modifications. Following existing paradigms and design patterns makes the behaviour of the software more predictable and makes results easier to replicate. By following the recommendations in this document, interoperability between software packages can be achieved.

The sections include requirements, as well as hands-on instructions and examples. They cover topics such as code repositories and collaboration, and in-depth development best practices, including testing and documentation, for both the R and Python programming languages. The final section offers guidelines for the creation of tutorials for the produced software. At the head of every section an overview is offered that summarizes the minimal requirements (MUST as per RFC 2119). The text of the section can include additional recommendations (SHOULD, RECOMMENDED as per RFC 2119).

Code repositories

All software code MUST be maintained on GitHub. Code is maintained in a repository, which contains all files, discussions and version history related to a single software package or analysis.

Create a repository

You first need to define the scope of your repository. An installable software tool (R package, Python library, etc.) MUST be maintained in its own repository. For an analysis, choose a scope that is easy to manage and collaborate on.

It is RECOMMENDED that you start your repository before you write code. That way, you can follow best practices, others can contribute and all version history is captured from the start.

The easiest way to create a repository is in your browser:

- Login to GitHub (https://github.com).

- Go to https://github.com/orgs/b-cubed-eu/repositories. If you do not see a

New repositorybutton (green), then you are not yet invited to the B-Cubed organization on GitHub. Email your GitHub username to GitHub B-Cubed admin and wait with the following steps until you are invited. - Follow the Quickstart for repositories instructions and create a new repository at https://github.com/organizations/b-cubed-eu/repositories/new:

- Choose

b-cubed-euas owner. If that option is not available, see step 2. - The repository name SHOULD be lowercase, dash-separated and short.

- The description SHOULD be a descriptive, one-sentence title (without period at the end), such as

R package to read and write Frictionless Data Packages. - The visibility MUST be set to

public. This makes it easier to collaborate and reference files and code. - Check

Add a README file. - You MUST select a

.gitignoretemplate (e.g. R, Python) - You MUST select a licence and you MUST set it to

MIT License. This conforms to the B-Cubed Data Management Plan.

- Choose

If you already have your code (locally), follow About adding existing source code to GitHub. Using GitHub Desktop is the easiest option.

If your code is already on GitHub under a personal account, it MUST be transferred to the b-cubed-eu organization or your institution, if it has a well-established track record of maintaining code on GitHub. Contact the GitHub B-Cubed admin to gain the rights to transfer your repository to the b-cubed-eu organization.

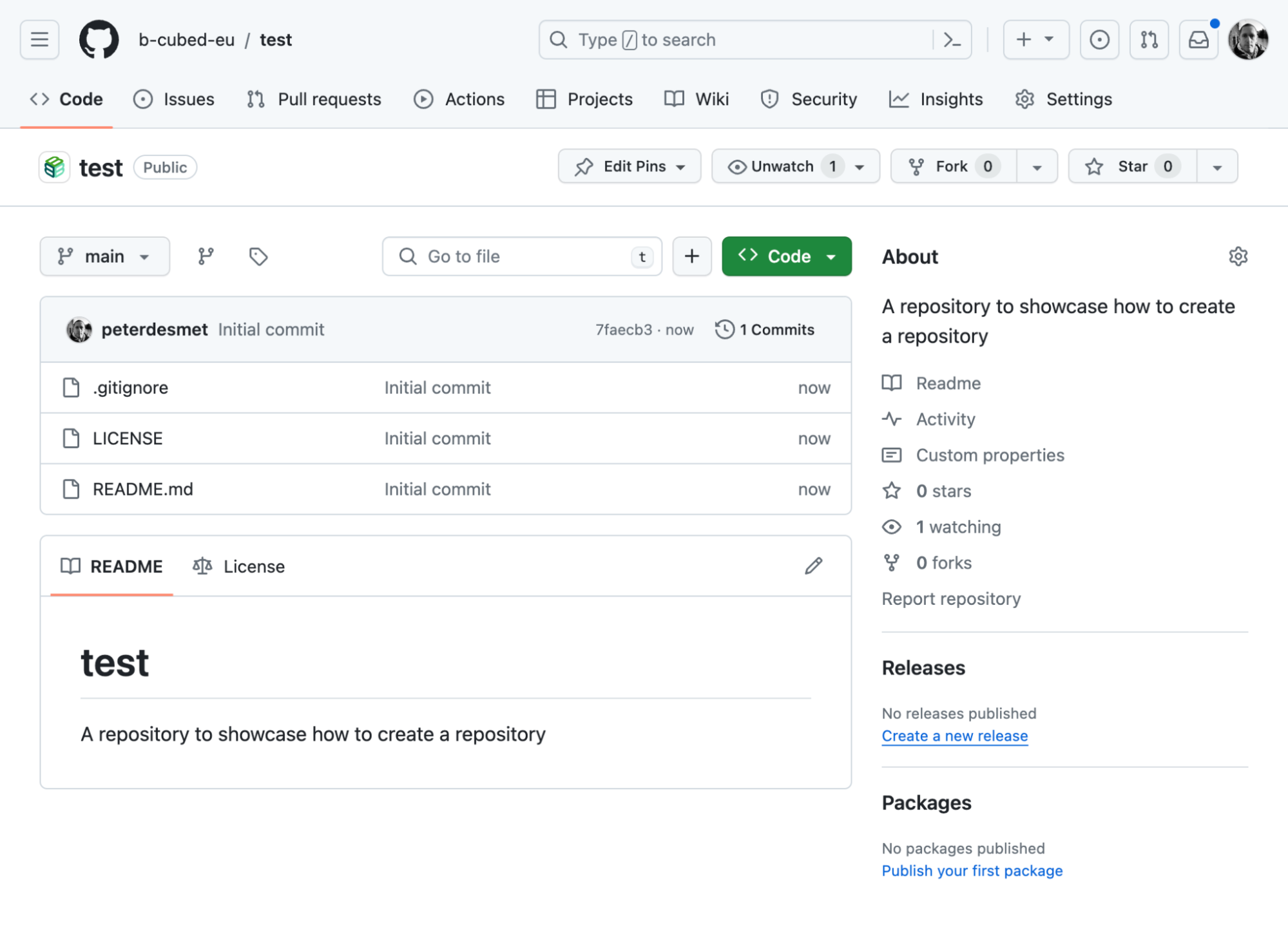

Once you have created a repository (see Figure 1), you SHOULD complete a number of additional steps.

Figure 1: Screenshot of a newly created repository.

Figure 1: Screenshot of a newly created repository.

Set the copyright holder

- Go to the

LICENSEfile. - Click the pencil icon.

- Select

Choose a license template. - Choose

MIT License. - Select the

yearthe software was started. - Set

Full nameto the institution where the maintainer of the software is employed (e.g.Research Institute for Nature and Forest (INBO)). When in doubt, leave asB-Cubed. - Commit the changes.

Ignore Mac .DS_Store files

Mac operating systems create .DS_Store files to store attributes of a directory. These can clutter your repository and should be ignored.

-

Go to the

.gitignorefile. -

Click the pencil icon.

-

Scroll to the bottom and add the following code (before the empty line):

# Mac OS.DS_Store -

Commit the changes.

Add a CITATION.cff file

Repositories MUST contain a CITATION.cff file so users know how to cite the software. Its metadata also gets picked up when depositing a repository to Zenodo (see releases. For more information see What is a CITATION.cff file or GitHub’s About CITATION files.

- Go to the main page of your repository.

- Click

Add filethenCreate new file. - Name your file

CITATION.cff. - An info box will appear, select

Insert example. - Include the name and ORCID of the maintainers.

- Remove the lines

doianddate-released. - Commit the changes.

Note: this file can be updated later (manually or through functions).

Note: a CITATION.cff is different from the R-specific CITATION file (without an extension).

Add topics

- Follow the Classify with topics.

- Add a number of topics, including the language (

randrstatsorpython), the type of software (e.g.r-package,analysis) and related subjects (e.g.invasive-species), cf. the section on GitHub repo topics in the rOpenSci Packages guide.

Hide irrelevant tabs

- Go to the

Settingstab. - In

Features, turn offWikisandProjects. These features will likely not be used.

Invite collaborators

- Contact the GitHub B-Cubed admin to indicate who you want to invite. The admin can then organize the collaborators in teams.

- Follow the Invite collaborators instructions (these are for personal repositories, but many of the steps apply to organization repositories).

- Type the GitHub name of the collaborator you want to add.

- Indicate the rights (

Read,Triage,Write,Maintain, orAdmin). - The collaborator will receive an email invitation to collaborate.

Extend your README.md file

See the README file sections.

Setup your local environment, contribute code and collaborate

See the Code collaboration section.

The README file

A README file communicates the most important information about your repository/software. It will serve as a welcome sign for users, meaning that it will be the first and maybe most important piece of metadata that users will encounter. It often also serves as the landing page for a documentation website.

Maintainers SHOULD extend a README beyond its initial template when it was created as soon as possible, as it helps to define scope and expectations and facilitates collaboration. General guidance on writing a README can be found in GitHub’s About READMEs or Make a README, while software languages (e.g. Python or R) often have specific instructions. Some suggestions for its contents are detailed in the sections below. See the README.md of the frictionless package as an example.

Format

The README file MUST be written in Markdown (and therefore be named README.md), unless the software language recommends otherwise. Python for example recommends structured text. See the GitHub’s Basic formatting syntax guide for more information on how to write Markdown.

Title

A README MUST start with an H1 title with the (human-readable) name of the repository/software. The title is generally the same as the name of the package, see Naming your package.

Badges

Right below the title you can optionally show badges or shields to convey the current development status, link to a publication or archive, test coverage and more. Many GitHub workflows come with a status badge and static shields can easily be created using https://shields.io/badges. Vincent A. Cicirello provides a general overview in this blog post.

Maintainers SHOULD at least include a repo status or lifecycle badge, to indicate the maturity/support for the repository/software. See repostatus.org for statuses or lifecycle and how to add it as a badge.

Description

Below the Title and the optional badges, a brief, title-less introduction MUST be provided, explaining the rationale and/or scope of the repository/software. A software package might initially limit its scope to only part of a bigger problem, and signal this in its description. For example a package wrapping an API might only support reading from that API, not writing to it. Or an analysis library might only initially offer statistical functionality, but not any visualization of results.

Installation instructions

While it can be very clear how to install a software package for those who were closely involved in writing them, the same is not always true for external users. Thus minimal instructions SHOULD be included in the README on how to install the software and its dependencies.

Examples or usage instructions

Similar to the installation instructions at least one example of the functionality of the analysis workflow or software SHOULD be included in the README.

README files for data

A repository can have additional README files beyond the one in the root. These typically serve as an introduction to a specific directory. These SHOULD NOT be used, as there are better ways to document code, but it can serve as a quick way to describe data files. See this guide by Cornell University Data Services or Dryad’s best practices document for guidance. Better yet is to deposit your data elsewhere.

Code collaboration

Open source software relies on collaboration. Participants in this process are not only developers, but anyone interacting with the software (code), such as maintainers, contributors, testers, users reporting issues, etc. To facilitate the collaboration process, it is good to adopt a number of community standards and best practices (see below).

For more information on open source software collaboration, see Finding ways to contribute to open source on GitHub (also useful for non-developers) and GitHub’s Open source guides. See how well your repository is adopting community standards at https://github.com/b-cubed-eu/<your-repo>/community.

Add a Code of conduct

A code of conduct is a document that establishes expectations for behaviour from all software participants. Adopting and enforcing it can help to create a safe and positive working space.

All software MUST have a code of conduct, as a CODE_OF_CONDUCT.md file following the Contributor Covenant template. All participants to software MUST abide by its code of conduct.

To add a CODE_OF_CONDUCT.md:

- Follow the Add a code of conduct instructions.

- In step 5, choose the

Contributor Covenanttemplate. - Add as

Contact method:b-cubedsupport@meisebotanicgarden.be(this email is monitored by MeiseBG staff). - Before committing the changes, change the file name to

.github/CODE_OF_CONDUCT.md.

Alternatively, you can complete these steps in R using:

usethis::use_tidy_coc()But update the default email address (codeofconduct@posit.co) in “Enforcement” to b-cubedsupport@meisebotanicgarden.be before committing the file.

Enable notifications

Notifications are (email) alerts of participant activity in a repository or issue thread you are subscribed to. They facilitate collaboration and relieve you from having to check into GitHub.com. Activities that can trigger a notification include issues, pull requests and releases. Commits do not trigger a notification, which is why the GitHub flow (i.e. pull requests) is recommended to inform collaborators of important changes. You also won’t receive notifications for your own actions.

You are automatically subscribed to notifications based on your actions (like commenting on an issue) or the actions of others (like @mentioning or assigning you). You don’t need to be an official contributor to be notified, anyone can do so by clicking the Watch button on a repository homepage. Maintainers MUST watch the repository they maintain. If you receive too many notifications, you can control what events you want to be notified of.

When receiving a notification by email, click the view it on GitHub link at the bottom to interact. This generally provides better context and formatting options than your email client (see Report issues).

Follow the GitHub flow

The GitHub flow is an easy-to-adopt practice for code collaboration that MUST be followed for all code contributions to B-Cubed software. It consists of making a branch, making changes, creating a pull request, addressing review comments, merging the pull request and deleting the branch. See GitHub flow for more information, including links to further documentation for all the steps.

Protect the main branch

The main branch MUST contain the software code in a state that can be installed without issue. To ensure code contributions (via pull requests) are reviewed before these are merged into the main branch, you can configure your repository to do so:

- Follow the Branch protection rule instructions.

- For

Branch name pattern, choosemain. Require a pull request before mergingSHOULD be enabled, with the defaultRequire approvals.

See also GitHub flow for working with branches.

Contributing guide

Maintainers SHOULD clarify how participants can contribute to their software, by adding a contributing guide as a CONTRIBUTING.md file in the .github directory.

To add a CONTRIBUTING.md file:

- Follow the Contributor guidelines instructions.

- Copy/paste a template such as Peter Desmet’s CONTRIBUTING.md or the Contributing to tidyverse.

- Adapt where necessary.

- Make sure the instructions do not contradict with the Github flow.

Alternatively, you can complete these steps in R using:

usethis::use_tidy_contributing()Which will use the Contributing to tidyverse template.

Report issues

While the GitHub flow lowers the barrier for making code contributions, it is useful (and saves you from writing unnecessary code) to interact with the maintainer(s) before suggesting changes. The easiest way to do so is by creating an issue.

Issues can be used to report and discuss a bug, idea or task. Issues are typically not used to ask for support in using the software. Anyone can create an issue or comment on it, and all participants watching the repository will get a notification. Once an issue is resolved (by fixing the bug, implementing the feature, or deciding not to act upon it) it can be closed. Closed issues are still accessible and can act as a history of decisions.

Writing a good issue takes skill, see this blog post or the tidyverse code review guide for guidance, and follow the contributing guide.

Just like the README file, issues (and pull request) support Markdown formatting that can improve readability, link issues to code and other issues, and notify people. See the GitHub’s Basic formatting syntax guide for more information.

As a maintainer, you can nudge participants in the right direction by providing an issue template. Follow the Configuring issue templates for your repository instructions to do so. Alternatively, you can complete these steps in R using:

usethis::use_tidy_issue_template()But update or remove the references to https://stackoverflow.com or https://community.rstudio.com before committing the file.

Local development

While some contributions can be made directly in the browser (one file at a time), most software development will be done locally, in an environment where it can be run and tested. Git (and the GitHub flow) allow these changes to be synchronized. Rather than explaining how to use git, we recommend the use of GitHub Desktop to facilitate this process.

GitHub desktop is a visual interface that allows you to commit your changes (include file parts and multiple related files), push those to GitHub.com, pull changes from contributors, resolve merge conflicts, and switch branches. It works well next to other code editors such as R Studio. See the GitHub Desktop instructions to get started.

Versioning

Code versioning (or version control) is an essential aspect of software development. It provides a mechanism to keep a detailed history of the changes that are made to the source code, as well as the decisions leading to those changes. This allows for a deeper understanding of the code and facilitates code audits/reviews. Code versioning also serves as a backup and recovery mechanism of the code. In case of critical errors or functionality loss, it is possible to revert to a previous working release of the software. Finally, versioning is an important communication mechanism for users of the software, especially software using it as a dependency. It indicates what changes can potentially break or alter existing functionality, offering the users the option to adapt their code or use a previous version.

Semantic versioning

Software MUST use semantic versioning, where the version number is of the form MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH. An example of version changes could be the following:

0.1 # First release0.2 # Minor release0.2.1 # Critical bug fix0.3 # Minor release1.0-rc.1 # Release candidate for version 1.01.0 # First release of the public API (i.e. the collection of user facing functions)1.1 # Minor release1.1.1 # Critical bug fix1.2 # Minor releaseThere is no semantic difference between x.y.0 and x.y.

Git commits

Versioning is built into git, where changes are expressed as commits. Try to create logical commits, where related changes are bundled together (and leave unrelated changes for a following commit). Document your commit with a concise commit message in the active tense (Add Pieter as contributor, Use 'invalid' over 'incorrect', etc.) and where necessary, document the reasoning in the commit description.

GitHub releases

Major and minor versions MUST have an associated GitHub release:

- Follow the Manage releases instructions.

- Use the semantic version number for the tag (e.g.

0.1,1.1.1)

Starting from release 1.0, authors MUST also publish their releases on Zenodo. Zenodo and GitHub are integrated, allowing this publication to be automated. See this tutorial for details.

Data products

The purpose of this section is to outline the requirements for software and scripts that are developed within the B-Cubed project. Data products are out-of-scope. However, many of the principles mentioned in this document can be applied to data products as well. For more details, we refer to the upcoming deliverable “D3.3 Guidelines on the FAIR and open depositing of data products to ensure that B-Cubed data cubes are compatible with the EBV Data Portal and other outlets for data cube dissemination”.

Changelog

To communicate and explain version changes, each repository SHOULD have a changelog. This changelog SHOULD be expressed as a NEWS.md file for R code (see the rOpenSci recommendations).

In R you can create a NEWS.md file using:

usethis::use_news_md()R

R is a programming language for statistical computing and data visualization.

- General guidance on how to use and write R can be found in Adler (2012) and Crawley (2012).

- For R packages, we refer to the rOpenSci Packages guide (rOpenSci 2021).

- For analysis code, we refer to the Software Carpentry’s fundamentals for reproducible scientific analysis in R (Zimmerman et al. 2019). More resources are listed on AGU’s Introduction to Open Science. The British Ecological Society guide on reproducible code and Stoudt et al. (2021) list principles, while Sandve et al. 2013 has rules for reproducible data analysis. Specifically for Data Science we recommend R for Data Science.

- For more information on the use of RMarkdown, see R Markdown: The Definitive Guide and Guidance for AGU Authors: R Script(s)/Markdown.

RStudio projects

R code is run in a specific context, with an associated working directory, history, etc. If that context is undefined or too broad, it can create conflicts between projects or make it hard for others to run your code.

To solve this, software MUST make the context explicit by including an RStudio project file (file with .Rproj extension) in the root of the repository to make the context explicit. This file will set your and everyone’s working directory at the root of the repository. In addition, software MUST only use relative paths starting at that project root to refer to files and MUST NOT use absolute paths. The implications of using absolute paths are described in the British Ecological Society guide on reproducible code. R code should strive to be as portable as possible, for example by never referring to a drive letter, network location or storage mounting point.

Further benefits of RStudio Projects are described in this section of the R Packages book. Software carpentry provides a guide on project management with Rstudio.

Dependencies

Please refer to the rOpenSci recommendations regarding dependencies.

Some recommendations for common use cases:

- HTTP requests: httr2, curl, crul

- Parsing JSON: jsonlite

- Parsing XML: xml2

- Spatial data: sf, do note that rgdal, rgeos and maptools are being deprecated, we thus advise against using sp. terra is preferred over raster, as it is being retired (see this blogpost). More information about the migration can be found on the r-spatial website, and this blogpost about the retirement of sp, rgdal, maptools and rgeos.

In general it is recommended to use packages from the tidyverse over base R functions in cases where the tidyverse alternative has significant advantages. For example the case of readr::read_csv() over base::read.table(). The readr alternative is faster, has better error handling, and is easier to use. However, certainly a case can be made for having as few dependencies as possible, and wrapping your own functions around base to get around certain limitations. The question on when exactly you should take a dependency, depends on the context. The R Packages book offers some guidance in this matter. Jeff Leek has written a blog post on his decision process: How I decide when to trust an R package and the tidyverse makes a case for not using internal functions from dependencies.

Adding a dependency to your DESCRIPTION file is easy using usethis:

usethis::use_package("dplyr")Refer to the rOpenSci recommendations for more suggestions.

Code style

Good coding style is like correct punctuation: you can manage without it, butitsuremakesthingseasiertoread. — R for Data Science

A number of useful packages exist to help you stick to the tidyverse style. To automatically modify your code to adhere to the recommendations, you can make use of styler which also exists as a plug-in for RStudio. To check your code for issues, you can use a liter, a popular choice for R is lintr. More information regarding code style can be found in the rOpenSci Packages guide in the section on code style, the tidyverse style guide. Hadley Wickham also offers some insight in his workflow when it comes to code style.

Testing

Have you ever written any code that turned out to not really do what you wanted it to do? Made a change to a helper function that introduced bugs in other functions or scripts using it? Or found yourself running the same little ad hoc tests in the console time and time again to see if a function is behaving as expected? These are all signs that you could benefit from using automated testing.

By writing tests that check the major functionality of your software, you are ensuring that changes along the line don’t break existing functionality. And that updates to underlying dependencies didn’t have unexpected consequences.

A general overview of the how and why of testing R code is found in R Packages book chapter testing basics. The rOpenSci Packages guides offers some helpful advice regarding tests in the section on testing. Other interesting resources include the blogpost by Michael Lynch on why good developers write bad tests, the documentation of testthat and covr. And rOpenSci also offers a book on HTTP testing. For more information on unit testing in general, you might find “Unit Testing Principles, Practices, and Patterns” by Khorikov (2020) a good resource.

Using testthat in practise

Start using testthat for an existing R project by running:

usethis::use_testthat()Which will create tests/testthat/ and tests/testthat.R, and adds the testthat package to the Suggests field.

Creating a test for an existing function is automated via usethis:

# Explicitly refer to the file we want to testusethis::use_test("filename_to_test")

# Or automatically if the file is already open and active in Rstudiousethis::use_test()While it is a good idea to regularly run your tests locally, it is also a good idea to automate this in the form of continuous integration:

# Runs R CMD CHECK which includes running all testsusethis::use_github_action("check-standard")

# Calculate the code coverage and reportusethis::use_github_action("test-coverage")You can also add badges to your README page to signal your R CMD CHECK status (which includes your unit tests) and test coverage:

usethis::use_github_action("check-standard", badge = TRUE)usethis::use_github_action("test-coverage", badge = TRUE)Tests can then be run by:

# For a packagedevtools::test()

# Or else, make sure your functions are loaded and thentestthat::test_dir("tests/testthat")Testing figures and plots

The goal of unit testing is to compare the output of a function to some expectation or expected value, however, for some outputs this isn’t very practical. One example is binary outputs such as figures or plots. While testthat offers a solution for this in the form of snapshots (and this is certainly a very powerful and useful feature), these snapshot tests are very sensitive to minute changes.

vdiffr is a package that forms an extension to testthat, it converts your visual outputs to reproducible svg files that are then compared as testthat snapshots. This offers some relief, but might still result in false positive test failures. After all, if your plotting library changes its rendering slightly, the test will fail.

A final option is to use a public accessor of your plotting library, for example ggplot2 offers a number of these assessors that allow you to test specific parts of every layer. This post on the tidyverse blog offers more insight on why you might want to go about testing this way.

Check your R code

There are several packages to check how well your R code is following best practices (from which many of the requirements in this document are derived):

- pkgcheck: follows rOpenSci recommendations.

- checklist: works for R packages and analyses, follows INBO recommendations.

- lintr: performs static code analysis to highlight possible problems, including good practises and syntax.

- styler: can automatically format code according to the tidyverse style guide.

- goodpractice informs about different good practices for packages.

- dupree identifies sections of code that are very similar or repeated.

R functions

There are a number of advantages to wrapping existing code into functions, as put by Nicholas Tierney in his excellent blog post on how to get better at R:

I don’t think I can overstate this, but learning how to write functions changed how I think about code and how I think about solving problems. — Nicholas Tierney

This same blog post also contains a simple example of how to turn existing code into a function. A more in depth description can be found in the section on functions in R for Data Science.

To summarize the why, you should use functions to:

- Create more readable code by placing difficult to understand code into functions.

- Avoid errors when reusing (copy/pasting) code multiple times over the same analysis.

However, using functions is not without its pitfalls. But many issues can be avoided by sticking to some ground rules:

Functions need to be self-contained, the reasoning behind is explained well in the section “writing functions” in the British Ecological Society guide on reproducible code. Practically this means:

- A function SHOULD NOT rely on data from outside of the function whenever possible.

- A function SHOULD NOT manipulate data outside of the function, thus it MUST NOT make changes to objects in the global environment. If you are importing data from the system to R, return an object rather than modifying the global environment (as is also explained in the tidyverse style guide).

- If it is necessary to make changes to data outside of the function, create a new file rather than making changes to an existing one. Functions that create new files MUST make this clear in their name, a good example is starting the function with write, for example

write_csv()from readr.

Keeping your functions separate from analysis code can improve the readability of the analysis, and ease the maintenance of the functions. It is considered best practice to place every function in its own .R file, and to name this file after the function. As described in the R Packages book. You can create such a file using:

usethis::use_r("function-name")And start your function using the included code snippet in RStudio.

A sure way to confuse users is for a function to return a different output with the same inputs/arguments, this is the case when some of the inputs are implicit. For example an option or locale setting, the system time or a local datafile that might have changed. Using implicit arguments can lead to difficult to trace behaviours across different computers, and makes a function more difficult to read. A notable exception is when there is an element of randomisation in the output, in this case it is a good idea to allow for setting the seed as a function argument to make this behaviour clear for the user and to allow for reproducible results. For more information about this, read this excellent section in the tidyverse design principles.

One of the best ways to improve your reach as a data scientist is to write functions. — R for Data Science

Further reading:

- An excellent overview of how functions actually work in R can be found in the section on functions in R for Data Science, the rest of the section also includes an excellent overview of best practices.

- Nicholas Tierney provides an easy to follow example of how functions can make your life easier and how to get started with writing them in this blogpost.

- Principles and strategies that come in handy when writing functions (and packages) are summarized in the tidyverse design principles.

- Berkeley offers an introduction to functions in its Introduction to the R Language presentation.

- Software Carpentry has an excellent course page on R functions.

How to split a script into functions

The process of taking an existing script and converting it into a collection of functions that make the workflow more flexible, easier to maintain and more efficient, is an example of code refactoring.

An often repeated principle in refactoring and software development in general is DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself), and while there are certainly situations where you should repeat yourself (see also AHA programming, arguments for repeating yourself in unit tests), avoiding repetition makes your code easier to maintain and understand. Functions are the most obvious tool we have to avoid repetition, with the equally important benefit that they can offer serious documentation benefits and can make it easier for existing software to be used flexibly in the future.

Looking at an existing script, it is useful to consider what every part actually does (rubber duck debugging can be a useful technique in this). These logical sections and their substeps are good starting points.

Encapsulate repeated code blocks, or logical subsections that perform a single task (especially if they do it multiple times) into functions, and place objects that can influence the output as arguments. This can be a bit of a judgement call, but things like input file paths, output file paths, filters on the data such as taxonomy or time, number of bootstraps, random seeds etc. make for ideal argument choices. Often an object keeps being passed from section to section undergoing transformations on the way, and finally resulting in some output. If this is the case, the data object MUST be the first argument. For more guidance on this step, refer to the section on arguments.

The Research Institute for Nature and Forest (INBO) has a coding club session on functions that has practical exercises on how to turn an existing script into functions, and even finally a package. You can find this session here. Jennifer Bryan presented on “code smells” in 2018 during the useR conference. Code smells are a useful tool to identify parts of code that contain bad practices and are good candidates for refactoring. This presentation is available on YouTube.

Naming functions

From the tidyverse style guide:

There are only two hard things in Computer Science: cache invalidation and naming things. — Phil Karlton

Use verbs to name functions whenever possible, this is a clear indication that a function does something, in contrast to other objects. For more guidance please refer to the tidyverse style guide section on functions. Keep in mind that the name of the function should describe what it does as closely as possible.

If you find this difficult, consider if your function isn’t doing too much. Ideally a function should only do one thing, and only return one thing.

Function arguments

Consistent naming of arguments across functions greatly improves user friendliness. For guidance on object naming, please refer to this section of the tidyverse style guide.

In the same vein, it is best practice to place the most important arguments first, because these will be used first. This practice is covered by the tidyverse design principles. Doing this, also signals to the user what arguments they should minimally provide. It is also a good idea to never provide defaults for required arguments, and always provide defaults for optional arguments, as covered by this tidyverse design principle. This pattern communicates to users which arguments are required, and which ones are not, without having to read the documentation.

Similarly, functions that return objects or data of the same type as their input, MUST place this input as their first argument. This also ensures that functions are as compatible with pipes as possible (in base R |> or magrittr %>%).

Other tidyverse design principles regarding function arguments:

Documenting functions

Functions that are well written can be considered partially self documenting, their name is an indication of what they do and their arguments tell the user what is expected and in what shape. However, apart from this adding additional information will make it much easier for your future self and others to reuse your code. R comes with this functionality built in in the form of .Rd files in the man/ folder. Instead of creating these files manually, this additional documentation MUST be written in the form of roxygen2 documentation, which takes the form of commented out text right above your function. The .Rd files are then rendered whenever you run:

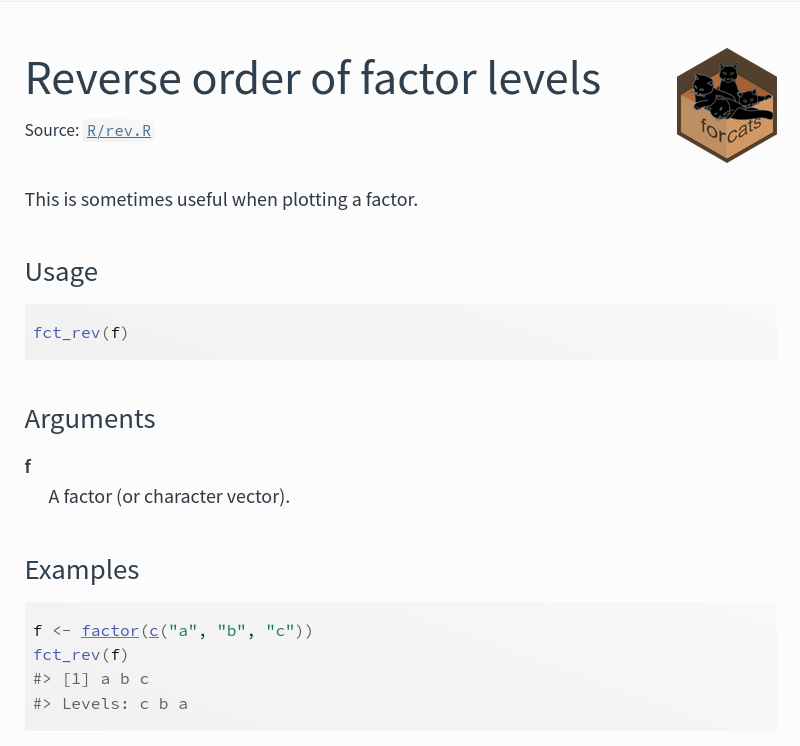

devtools::document()It is recommended that you add at least one example of the basic functionality of your function in the roxygen2 documentation. A very minimal example that uses roxygen2 documentation is the fct_rev() function from forcats:

#' Reverse order of factor levels#'#' This is sometimes useful when plotting a factor.#'#' @param f A factor (or character vector).#' @export#' @examples#' f <- factor(c("a", "b", "c"))#' fct_rev(f)fct_rev <- function(f) { f <- check_factor(f)

lvls_reorder(f, rev(lvls_seq(f)))}An additional advantage of this system is that every function will automatically get its own page on your documentation website. A screenshot of the webpage that was created for the function above is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Screenshot of the online documentation of the forcats function

Figure 2: Screenshot of the online documentation of the forcats function fct_rev().

If you are new to documenting functions, have a look at the chapter on function documentation in the R Packages book. There is also the getting started page of roxygen2, and finally the rOpenSci Packages guide offers some advice in the section about documentation.

R packages

Hadley Wickham and Jennifer Bryan have written an excellent guide on R Packages, that comes highly recommended. This document goes through all the required steps to creating a package. More advanced is the R projects manual on writing R extensions. Hadley Wickham has included sections on functional and object oriented programming in his book Advanced R that might come in useful.

A lot of the tooling around R packages is also useful for R analysis code formatted as a script. However, while it might look intimidating at first, authoring an R package isn’t nearly as difficult as it might seem. Below there is an included example of R commands that set up an R package, and the required documentation, create a first function, tests for that function, update the documentation and run the package tests. All of this can be done equally well for a script, but this requires a lot more manual work.

# Starting a minimal R package --------

## Setup everything we need in a single line, isn't usethis amazing?usethis::create_package("packagename")

## We will be using GIT for our version controlusethis::use_git()

# Further repository setup according to guidelines --------

## Add an MIT licence fileusethis::use_mit_license(copyright_holder = "institution name")

## Tell the world how to contributeusethis::use_tidy_coc()usethis::use_tidy_contributing()

## Write a README, in Rmd format if we want to show off our codeusethis::use_readme_rmd()## Let's use github actions for some automationusethis::use_github_action("check-standard", badge = TRUE)usethis::use_github_action("test-coverage", badge = TRUE)

# Let's write our first function --------

usethis::use_r("cool_function_name")

## And add a test for it too!usethis::use_testthat()usethis::use_test()

## Update the documentationdevtools::document()

## Run all the testsdevtools::test()Naming your package

Naming a package or analysis script can be difficult. rOpenSci offers a number of recommendations on this topic. To check if your package name is available, you can use the available package, which can also inform you about possible other interpretations of the name, including possibly offensive ones.

available::available("mycoolpkgname")Nick Tierney also gives an interesting overview of trends in naming packages. Yihui Xie makes an excellent case for easy to type names without too many case changes.

Creating metadata for your package

The CodeMeta project defines a codemeta.json metadata file (in JSON-LD format) that helps machines interpret information about your package. This is useful because it can ease the attribution, discoverability and reuse of your code beyond the tools already present in the R ecosystem. A codemeta.json makes it more likely someone will find your software who doesn’t know where to look for it, and that you’ll get credit for it when it is reused by allowing different metadata standards to be translated into each other via codemeta. The CodeMeta project makes a strong case for its inclusion in repositories. And so does rOpenSci.

Creating such a file is also very easy as it can be generated from the information already present in your README, DESCRIPTION and CITATION files. From the root of your package run:

codemetar::write_codemeta()Console messages

Sometimes a package needs to communicate directly with its user, this is usually done through either message(), warning() or stop(). The rOpenSci Packages guide advises against using print() or cat() because these kinds of messages are much more difficult for the user to suppress. Additionally, these kinds of messages are also more difficult to write good tests for.

Apart from base R, the package cli comes recommended for its many useful tools regarding good looking command line interfaces. Functions from cli also offer some advantages when used in assertions within functions over the popular assertthat and stopifnot() from base. Please refer to the documentation of cli_abort() here. A practical example of how you could use cli instead of assertthat can be observed in this commit on the frictionless R package.

README

For general instructions, see the README file section. The README file for R packages largely takes the same form as the one required for all repositories. Additionally, a number of useful tools are available to you as a developer to create a great README.

If you don’t have a README yet, you can create one with usethis:

usethis::use_readme_md()If you want to include code and its output in your REAMDE, you can instead create a README.Rmd in R markdown, and then render that to a traditional README.md file. Again, you can create one with usethis:

usethis::use_readme_rmd()This will not only create a README.Rmd, but also add some lines to .Rbuildignore and create a Git pre-commit hook to help remind you to keep README.Rmd and README.md synchronized. After you’ve made changes to README.Rmd, remember to update README.md by running:

devtools::build_readme()Adding badges to the README file

Usethis includes some useful functions you can use to add badges to your README file, for example for the lifecycle of your software:

usethis::use_lifecycle_badge(stage = "stable")Some other functions within usethis will also allow you to add a badge to your README, for example you can advertize your code coverage using the test-coverage action:

usethis::use_github_action("test-coverage", badge = TRUE)Documentation website

A documentation website allows (potential) users to learn about your package and its functionality without having to install it first. Luckily, prior knowledge of web development is not needed to create a documentation website for R packages. It can be generated automatically with pkgdown, which will pull the information you already included in the README file and function documentation. The introduction page of pkgdown describes its basic use (the documentation website of pkgdown was created with pkgdown). Here’s how to get started:

# Run once to configure package to use pkgdownusethis::use_pkgdown()# Run to build the websitepkgdown::build_site()By default, your website will include a homepage and a function reference, but there are several more pages you can add. The most useful ones are articles (called “vignettes”) to explain a certain functionality or workflow in a more tutorial-like fashion:

# Create a vignetteusethis::use_vignette("vignette-title")Since vignettes are included in the source code, users can also consult them when offline (in RStudio):

# Loading a vignette from dplyr (works offline too)library(dplyr)vignette("in-packages")# This is the same page as https://dplyr.tidyverse.org/articles/in-packages.htmlSince we are using GitHub to host our code, deploying a website is fairly straightforward:

usethis::use_pkgdown_github_pages()Neal Richardson posted a step by step guide on using pkgdown on his website. rOpenSci also offers some guidance in their chapter on pkgdown.

DESCRIPTION and authorship

The DESCRIPTION file includes, among others things, a list of all authors and contributors to the package. Apart from information about the authors, it also includes vital metadata about the version, licence and purpose of the included code. This file thus forms an important piece of metadata for the code it describes. This is also another place to refer to any external resources, such as the github repository where users can file bug reports or URLs to any external web APIs that may be called.

To uniquely identify the contributors to the software, it is very useful to include ORCID identifiers under the Authors in the description. The benefits of which are described on this rOpenSci blog post. An example:

Authors@R: person( "Pieter", "Huybrechts", email = "pieter.huybrechts@inbo.be", role = c("aut", "cre"), comment = c(ORCID = "0000-0002-6658-6062"))Further guidance on editing DESCRIPTION files can be found in the chapter on package metadata in the R Packages book. A more detailed overview can be found in the R project manual on writing R extensions.

CITATION

R packages commonly include a CITATION file (no extension) that provides information about how the package should be cited. See the CITATION file section in the rOpenSci Packages guide for guidance. This file can be created with:

usethis::use_citation()And users can retrieve its information with:

citation("package-name")All repositories MUST also include a CITATION.cff file (see Add a CITATION.cff file. You can keep it in sync with the CITATION file using a GitHub action provided by the cffr package.

rOpenSci offers a useful blog post on how to cite R and R packages that is a good read for both software authors and users.

LICENSE

As described in the Create a repository section, all software produced in the context MUST be licenced under the MIT licence. The copyright holder of the software will be the institution that will be maintaining the package, not the authors of the package.

Adding this LICENSE file is easy with usethis (take care to immediately set the copyright holder, as it will default to the package authors):

usethis::use_mit_license(copyright_holder = "institution name")This function will also set the License field in the DESCRIPTION file. For more information on package licensing, refer to the section on licensing in the R Packages book.

Examples

Examples show users how to use your software, and will often be the first thing people look at when they have trouble reusing your code. Thus including them not only fills an educational niche, but also provides a nice piece of documentation.

All functions intended to be used by users (i.e. public functions) MUST have an example in their roxygen2 documentation. But even for analysis code or workflows, including an example can be very helpful. More complex examples (or example workflows) SHOULD be included in a vignette. Every repository that contains R code MUST at least have one vignette.

Creating a vignette is automated by usethis, Keep in mind this will not work if you don’t have a DESCRIPTION file:

usethis::use_vignette("vignette-title")Dependencies

Dependencies are other packages your package relies on. Those need to be defined in the DESCRIPTION file, so that they are automatically installed when a user instals your package. You can use usethis to add a dependency to your DESCRIPTION:

usethis::use_package("package-to-depend-on")This will add a package to the Imports section of the DESCRIPTION file. The function also allows you to set it to Suggests instead, or to declare a minimum package version. Declaring a minimum version of a dependency isn’t usually necessary and should only be done as a continuous choice. For more guidance on the tradeoffs and decisions around dependencies, read the section on package dependencies in the rOpenSci Packages guide.

The difference between Imports and Depends is that while both are installed together with the package, Depends are also attached to the global environment, thus opening the door to all kinds of trouble. For example, if your package Depends on dplyr it will overwrite the stats function filter() which is loaded by default, because dplyr includes a filter() of its own. This kind of namespace conflict should be handled with caution, and avoided whenever possible. Code written by the user should behave as they expect, regardless of the order in which they load packages. Dependencies declared in Imports are not attached, thus avoiding this problem entirely. This principle and several other good practices are described in the section on package dependencies in the rOpenSci Packages guide.

When calling a function from a dependency, the dependency MUST be explicitly mentioned using package::function(). This makes it easier for collaborators to understand your code and it helps when searching for functions of a specific dependency:

# Badmy_function <- function(file) { read_csv(file)}

# Goodmy_function <- function(file) { readr::read_csv(file)}For dependency recommendations, see the dependencies section in the R section.

R analysis code

An important note is that most R analysis scripts could be wrapped as a package. This has many advantages:

- Packages provide a better structure.

- Packages are easier to install and use.

- Packages allow for better documentation.

- It is much easier for others to reuse your work.

- There are a lot of tools that can help you make your work more reproducible that work better in the context of an R package.

- Within B-Cubed and the wider R community there are people ready to help, so if you’ve been waiting for an opportunity to learn: this is it.

Creating an R package might seem like a huge step if you haven’t done it before, and while there is a learning curve, it really isn’t nearly as hard as it seems. All of this to say, please don’t be afraid to start an R package instead of an analysis script as part of your analysis workflow.

For more information on packages, refer to the R packages section.

An R analysis script/project can be started from scratch via usethis:

usethis::create_project("myprojectname")This automates a number of steps:

- It creates a new directory for your project to live in.

- It sets the RStudio active project to the new folder.

- It creates a new subdirectory

R/for R code to live in. - It creates an

.Rprojfile. - It adds

.Rproj.userto.gitignore. - And finally it opens your new project in a new RStudio window.

As a next step you could initiate git:

usethis::use_git()Python

Many of the principles that are outlined in the sections on R and R packages, also apply to writing Python code. In this section, we will outline some additional requirements for Python. A very good reference to Python programming can be found in The Hitchhicker’s Guide to Python.

Repository structure

After creating a new code repository, the preferred structure for a repo named sample is as follows:

.gitignorerequirements.txtREADME.mdLICENSEMakefilesetup.pypyproject.tomlsample/ __init__.py core.py helpers.pytests/ tests_basic.py tests_advanced.pydocs/ index.rst conf.py requirements.indata/ mydata.csvCHANGE.mdCITATION.cff.github/ CODE_OF_CONDUCT.mdVirtual environments

You MUST use a virtual environment to develop your Python code. Virtual environments provide control over the version of Python and the installed packages. This will also make it easier to create a requirements.txt. There are several options to do this, but it is recommended to either use virtualenv or conda.

Dependencies

All Python projects MUST contain a requirements.txt file containing all dependencies of the code. A guide on the preparation of this requirements file can be found in this documentation. The requirements file guarantees that the code can be executed in a reproducible manner. Also, when creating a Python package, this allows PIP to install all dependencies together with the package.

Code style

Python code must adhere to the PEP 8 style guide for Python code. Some of the main elements that should be taken into consideration when writing code are outlined below.

Use explicit code

The most explicit and straightforward way of coding is preferred. E.g.:

# Baddef make_complex(*args): x, y = args return dict(**locals())

# Gooddef make_complex(x, y): return {'x': x, 'y': y}One statement per line

Although in some particular cases it might be reasonable to have multiple statements per line, in general this is bad practice to have more than one disjointed statement on one line:

# Badprint("one"); print("two")

# Goodprint("one")print("two")Line breaks with binary operations

In order to improve the readability of the code, it is recommended to use line breaks before the binary operator:

# Badincome = (gross_wages + taxable_interest + (dividends - qualified_dividends) - ira_deduction - student_loan_interest)# Goodincome = (gross_wages + taxable_interest + (dividends - qualified_dividends) - ira_deduction - student_loan_interest)Check your code against PEP 8

It is recommended that each piece of Python code is checked using pycodestyle. Your code can be checked by using:

pycodestyle --first yourcode.pyFor more advanced usage of the package, please refer to its documentation website.

Testing

In general, testing should be performed on small units of functionality. As a good practice, it is recommended that each function has a corresponding test associated with. All testing MUST be performed using the pytest package. Several guidelines on using the package are available on its documentation website.

Another good practice is to include a test for each bug that is/was present in the code. In that case, please refer to the corresponding bug report in the test documentation.

Packages

Although there might be several use cases where it is sufficient to develop a Python module (single file), it is RECOMMENDED to package your code into a Python package. A comprehensive guide to creating a Python package can be found here. When adhering to the recommended repository structure, many of the requirements for a Python package are covered.

Documentation

Documentation for your packages MUST be created using Sphinx. Sphinx is a very powerful documentation generator tool which is widely used within the Python community.

The way Classes and functions are documented is using docstrings. A Sphinx docstring has the following structure:

"""[Summary]

:param [ParamName]: [ParamDescription], defaults to [DefaultParamVal]:type [ParamName]: [ParamType](, optional)...:raises [ErrorType]: [ErrorDescription]...:return: [ReturnDescription]:rtype: [ReturnType]"""Continuous integration with GitHub Actions

GitHub Actions SHOULD be used to test, build and release your Python packages. A step-by-step guide to publish your releases can be found here.

Tutorials

To make software more welcoming to users, each package and analysis MUST have at least one tutorial guiding users through its main functionality. These tutorials MUST be included (copied or referenced) in the B-Cubed guides and tutorials website.

Documenting software and code in B-Cubed

Tutorials MUST be written in English and presented as literate programming documents (e.g. Jupyter notebooks, RMarkdown or Quarto) to provide both narrative context and executable code snippets. The documentation website will be versioned and an automated testing mechanism will be set up to guarantee that provided documentation works for a specific release of the B-Cubed toolbox. Ensure that your tutorial passes automated tests.

Creating a new tutorial

-

Create a new branch in https://github.com/b-cubed-eu/documentation following the Github flow.

-

Browse to the

pagesdirectory or use this link. -

Click

Add fileand thenCreate new file. -

Name your file. Use lowercase and dashes (e.g.

create-occurrence-cube.md). -

Start your Markdown file with the following metadata, expressed in front matter, between two

---lines:---title: Your tutorial titledescription: Short description of your tutorial (will appear below title)author: Your name (if there are co-authors, use "authors:" and comma-separate them)citation: >A full citation for your tutorial if useful (this will be used instead of author or authors)permalink: /name-of-your-tutorial/---Start of tutorial text ... -

Commit the changes.

You now have a template for writing your tutorial. It might be easier to continue locally, using GitHub Desktop.

Writing your tutorial

You can write your tutorial directly in the Markdown file, but if it includes code snippets, it is RECOMMENDED to write it as a reproducible R Markdown, Quarto or Jupyter Notebook. This makes it easier to run and test (cf. a README.Rmd over a README.md). Such files can then be rendered to HTML/Markdown, and will not only include the text and the code snippets, but also the results of running the code (example). That rendered HTML/Markdown can be copied to the Markdown file, under the front matter. The original R Markdown, Quarto or Jupyter Notebook should be maintained in a separate repository, not in the documentation repository.

Place any images in the assets/images directory. Start their file name with the name of your tutorial or place them in a subdirectory. Link to the images from your tutorial as .

As for the content of your tutorial:

- Clearly state the purpose of the tutorial.

- Include step-by-step instructions on how to install the software.

- Specify dependencies and system requirements if applicable.

- Detail how to use the software.

- Include at least one example and explain key features.

- Write in a clear and concise manner for a diverse audience.

Once your tutorial is ready, submit your branch as a pull request for review.